Data Beings

About

Data Being essay serves as a starting point for investigating various phenomena resulting from human and non-human relation to data.

Humans as data beings

Extended or reduced?

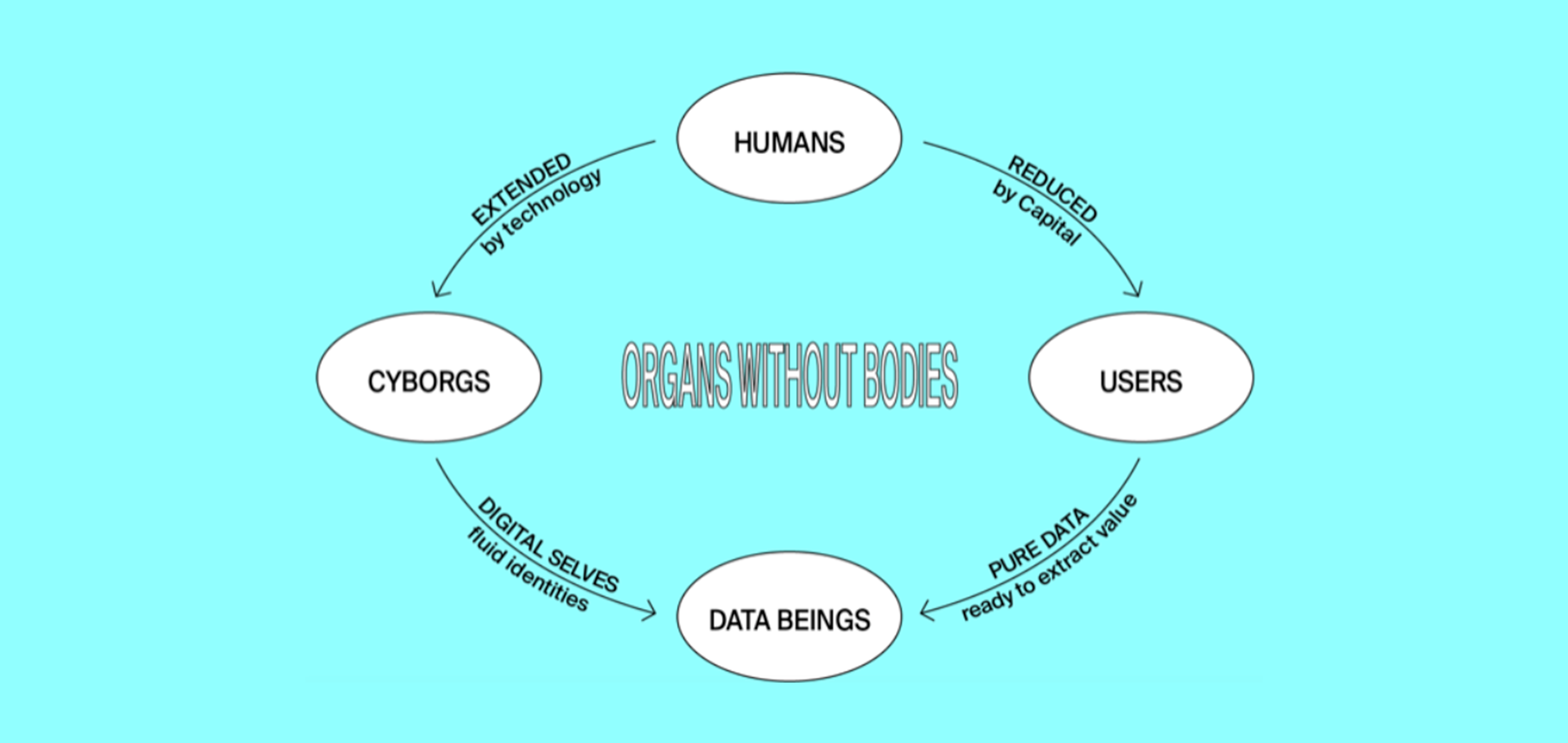

Through technology, human senses and knowledge have been extended ︎ hate it or love it ︎we became cyborgs. Human identity in western societies has never been more fluid than now. Thanks to our profiles on forums, games or social media, we can endlessly create new versions of our digital selves. Parallelly to the extension, capitalism first reduced humans to users ready to be exploited, then into pure data enabling more ubiquitous ways to extract value from people’s individual and social actions.In both cases we start the journey from the position of the physical body to be digitally represented, defragmented and scattered around. Our data – organs without bodies are constantly flowing in cyberspace. But this seemingly non-physical matter has a very physical form. We are collectively humming in muggy server basements, warehouses, farms. The electrical hum has become the anthem of a new generation of humans – data beings.

What I mean by “data being” is the combination of a physical & cognitive manifestation of human being, the whole set of its defragmented digital representations and their physical infrastructure. The result of this whole process, the journey, the constant flux of extension & reduction with its materiality & immateriality I call “data being”.

To recognize the meaning of our data, to build a close connection with our digital selves, to rethink our data relations is one of the major challenges in examining 21-century’s power dynamics. I see the acknowledgement of humans as data beings as the first step into a deeper analysis of our contemporary condition.

Economics of data beings

The first attempt to evaluate a single human life was through necroeconomics during The Great Plague. “The value of a statistical life (VSL) is the local trade-off rate between fatality risk and money.” (2019, Kniesner, Viscusi). Following this idea in the Digital Age we ask what is the value of our digital life? Analogically to the past, it is based on a speculative measurement. According to the Marxist labour theory of value, workers are selling their labour-power – a speculative measurement of a person's capacity to produce commodities – they are trading their effort. The evaluation of our data follows a similar rule of speculation – it is a prediction of one’s buying power. So what is the value of our data, does it mean that our data is worthless after we die? An average person’s data is worth less than 1$, the most valuable is the rarest one – extracted from wealthy people. Therefore, the value of our data has become a reflection of the class struggle. Whether it is leisure time, shopping or even sleeping, through hardware and software we are constantly producing data which can be commodified without limits.Some say that you can simply not use Social Media platforms, avoid free apps and platforms which harvest your data, but in fact, it is an illusionary choice. Being invisible and refusing to use tech giant platforms like Google is a new privilege which barely anyone can afford. The Vectoralist Class made themselves the owners of our data, digital bodies, organs and nervous system. This self-given agency began new forms of digital exploitation – data colonialism and neo-feudalism.

Neo Feudalism and the double power relation

Is it possible that despite the whole “what comes after capitalism?” discussion, we have already stepped into a new mode of production? As Jodie Dean claims, we might be entering something much worse – neo-feudalism. In this new-old structure, we can observe two groups: new lords and new peasants. The owners of communication platforms who are harvesting and capitalising on our data are an example of the new lords. Collecting digital data became a new form of exercising power. If we look closer at dataveillance as an important and ubiquitous part of the contemporary work environment we could see an interesting dual power relation. The first one results from the financial dependence between the worker and the business owner. The second one is the consequence of employee data collected and managed by an employer.In Industrial Capitalism, the employer was buying the worker’s time and labour-power, but not the worker’s body. Now through dataveillance, an employer has access to and owns the worker’s digital body.

We can manage only this what can be measured – the perverse nature of quantification combined with technological advancement lead us to different types of dataveillance at the workplace. The most popular, especially during the shift to remote working following the lockdown, is employee monitoring software also called tattleware. It allows the employer to monitor employees: communication, browser searches, take screenshots every 15 seconds, measure “productivity”, social media activity (posts, comments etc), file transfers, printing, Keystrokes, GPS tracking. Some of the software vendors promote extra functionalities such as tracking the behavioural patterns of the most productive workers to replicate them through psychological manipulation such as Nudging. Biosurveillance at work manifests itself often through corporate wellness programs handing out to workers, usually voluntarily, wearables such as Fitbits which track different features of their physiology. AI voice surveillance software offer Cogito company advises call-centre workers how to speak to customers in a more “empathetic” way. The most radical example I found was the monitoring of brain activity of factory workers and military in China with the use of wireless sensors built into their headgear.

Donna Haraway “Cyborg Manifesto”

What I mean by “data being” is the combination of a physical & cognitive manifestation of human being, the whole set of its defragmented digital representations and their physical infrastructure. The result of this whole process, the journey, the constant flux of extension & reduction with its materiality & immateriality I call “data being”.

To recognize the meaning of our data, to build a close connection with our digital selves, to rethink our data relations is one of the major challenges in examining 21-century’s power dynamics. I see the acknowledgement of humans as data beings as the first step into a deeper analysis of our contemporary condition.

Economics of data beings

The first attempt to evaluate a single human life was through necroeconomics during The Great Plague. “The value of a statistical life (VSL) is the local trade-off rate between fatality risk and money.” (2019, Kniesner, Viscusi). Following this idea in the Digital Age we ask what is the value of our digital life? Analogically to the past, it is based on a speculative measurement. According to the Marxist labour theory of value, workers are selling their labour-power – a speculative measurement of a person's capacity to produce commodities – they are trading their effort. The evaluation of our data follows a similar rule of speculation – it is a prediction of one’s buying power. So what is the value of our data, does it mean that our data is worthless after we die? An average person’s data is worth less than 1$, the most valuable is the rarest one – extracted from wealthy people. Therefore, the value of our data has become a reflection of the class struggle. Whether it is leisure time, shopping or even sleeping, through hardware and software we are constantly producing data which can be commodified without limits.Some say that you can simply not use Social Media platforms, avoid free apps and platforms which harvest your data, but in fact, it is an illusionary choice. Being invisible and refusing to use tech giant platforms like Google is a new privilege which barely anyone can afford. The Vectoralist Class made themselves the owners of our data, digital bodies, organs and nervous system. This self-given agency began new forms of digital exploitation – data colonialism and neo-feudalism.

Neo Feudalism and the double power relation

Is it possible that despite the whole “what comes after capitalism?” discussion, we have already stepped into a new mode of production? As Jodie Dean claims, we might be entering something much worse – neo-feudalism. In this new-old structure, we can observe two groups: new lords and new peasants. The owners of communication platforms who are harvesting and capitalising on our data are an example of the new lords. Collecting digital data became a new form of exercising power. If we look closer at dataveillance as an important and ubiquitous part of the contemporary work environment we could see an interesting dual power relation. The first one results from the financial dependence between the worker and the business owner. The second one is the consequence of employee data collected and managed by an employer.In Industrial Capitalism, the employer was buying the worker’s time and labour-power, but not the worker’s body. Now through dataveillance, an employer has access to and owns the worker’s digital body.

Data beings at work

We can manage only this what can be measured – the perverse nature of quantification combined with technological advancement lead us to different types of dataveillance at the workplace. The most popular, especially during the shift to remote working following the lockdown, is employee monitoring software also called tattleware. It allows the employer to monitor employees: communication, browser searches, take screenshots every 15 seconds, measure “productivity”, social media activity (posts, comments etc), file transfers, printing, Keystrokes, GPS tracking. Some of the software vendors promote extra functionalities such as tracking the behavioural patterns of the most productive workers to replicate them through psychological manipulation such as Nudging. Biosurveillance at work manifests itself often through corporate wellness programs handing out to workers, usually voluntarily, wearables such as Fitbits which track different features of their physiology. AI voice surveillance software offer Cogito company advises call-centre workers how to speak to customers in a more “empathetic” way. The most radical example I found was the monitoring of brain activity of factory workers and military in China with the use of wireless sensors built into their headgear.

Bibliography

Zygmunt Bauman “Individual and society in the liquid modernity”

Deborah Lupton “Digital Bodies”

Shoshana Zuboff – Surveillance Capitalism theory

Emma Charles: White Mountain, video, 2016

Melanie Swan “Philosophy of Big Data – Expanding the Human-Data Relation with Big Data Science Services”

Marion Brivot, Yves Gendron “BEYOND PANOPTICISM: ON THE RAMIFICATIONS OF SURVEILLANCE IN A CONTEMPORARY PROFESSIONAL SETTING”

Deleuze Guattari – “body without organs” concept

Slavoj Zizek – “organs without body” concept

J. Kniesner, W. Kip Viscusi “The Value of a Statistical Life Thomas” “Data colonialism” Nick Couldry and Ulises A. Mejias “Communism or Neo-Feudalism?” Jodi Dean Neofeudalism: The End of Capitalism?

“Capital is Dead” McKenzie Wark

“How much is your personal data worth?” Financial Times,

Emily Steel, Callum Locke, Emily Cadman and Ben Freese“THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HEALTHCARE & THE DARK WEB” “Data Valuation — What is Your Data Worth and How do You Value it?” by ODSC - Open Data Science

“How can you measure the worth of your data?” — Quartz

Dark Web data trade

“Communism or Neo-Feudalism?” Jodi Dean

“Data colonialism” Nick Couldry and Ulises A. Mejias“Capital is Dead” McKenzie Wark

Employee monitoring tools research https://www.are.na/kat-zavada/employee-surveillance-t0_0ls

China is monitoring employees' brain waves and emotions — and the technology boosted one company's profits by $315 million

“Two-Stream Emotion Recognition For Call Center Monitoring”, Purnima Gupta, Nitendra RajputThis Call May Be Monitored for Tone and Emotion, Tom Simonite

How Fitbit Became The Next Big Thing In Corporate Wellness

“Limitless Worker Surveillance”, Ifeoma Ajunwa, Kate Crawford, and Jason Schultz All sources you can find here: https://www.are.na/kat-zavada/humans-as-data-beings-materials